In response to the COVID-19 outbreak and the resulting confinements, telework has been used extensively in many countries. However, it has been noted that it is not uniform across different occupations: economists Jonathan Dingel and Brent Neiman1 have shown that higher-skilled workers can telework more. This difference may have consequences in terms of inequality: those with jobs requiring less skills are less prone to telework and are likely to be more vulnerable: they would be furloughed or fired if they cannot exercise their tasks.

This difference in “teleworkability” depending on qualifications also has implications on employment geography.

However, this difference in “teleworkability” depending on qualifications also has implications on employment geography in a country such as France and these implications may be able to reawaken the geographical cleavages that France has experienced in recent years.

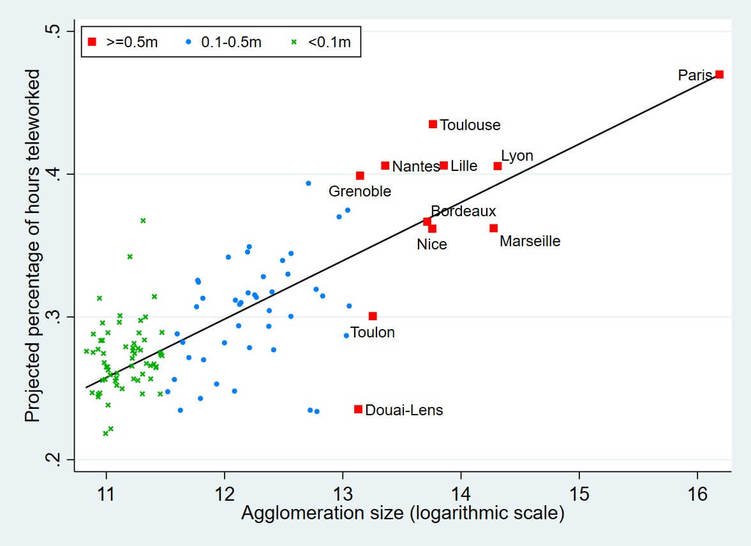

Using Dingel and Neiman's measures of telework capability by job type, we were able to calculate the predicted share of positions that could allow for teleworking for each French agglomeration (Figure 1) of over 50,000 inhabitants. While this proportion is around 40% on average for cities with more than 500,000 inhabitants, or even 50% for the Paris area, it hardly exceeds 30% for cities with 100,000 inhabitants.

Figure 1: share of jobs potentially tele-workable as a function of city size (log-scale)

The implication of this different exposure is that larger cities are more likely to adapt to confinement and potentially persisting social distancing measures afterwards. In contrast, smaller cities are less likely to adjust and, among other adverse consequences, unemployment there is likely to increase more sharply as government furloughing schemes run out in the next months.

Smaller cities are less likely to adjust and unemployment there is likely to increase more sharply as government furloughing schemes run out in the next months.

Thus, the ability to telework is likely to contribute to the exacerbation of geographical disparities between small and larger cities. These had been at the heart of the debates to understand the mobilisation of "gilets jaunes".

Notably, the different exposure to telework is already a result of these geographical cleavages. Larger cities telework mainly because they are richer in high-skilled jobs. In fact, these large cities have become significantly richer in skilled jobs over the past decades. For example, Paris saw the percentage of managers and engineers (“cadres”) in total employment increase from 23% to 36% between 1994 and 2015. This divergence of large cities from the rest of France was due to the arrival of new technologies and the greater possibility to displace or destroy less qualified jobs in these large cities2.

If the possibility of teleworking allows workers with skilled jobs to better cope with the short-term turbulences linked to the COVID-19 pandemic, it can also backfire in the longer term.

But, paradoxically, if the possibility of teleworking allows workers with skilled jobs to better cope with the short-term turbulences linked to the COVID-19 pandemic, it can also backfire in the longer term. If firms have successful telework experiences - that is, small losses of productivity related with working from afar, they may conclude that some jobs no longer need to be kept in larger cities and can be relocated, even abroad. Therefore, the same factors that led to skilled employment growth in large cities may now lead to the relocation, devaluation or elimination of at least some of these jobs, those for which physical presence or ideas exchange is less necessary.

1"How Many Jobs Can be Done at Home?" (on VoxEU); "Covid Economics: Vetted and Real-Time Papers" (on CEPR), 5 April 2020

2See Donald R. Davis, Eric Mengus, Tomasz K. Michalski, 2020, “Labor Market Polarization and the Great Divergence: Theory and Evidence” NBER working paper 26955. See the non-technical summary on VoxEU.