In “Can Unemployment Insurance Spur Entrepreneurial Activity? Evidence from France”, we study the impact of unemployment insurance on business creation in the context of a large-scale reform that took place in France in 2002, known as “Plan d’Aide au Retour à l’Emploi (PARE)”. The reform aimed at fostering business creation by unemployed people.

When unemployment insurance discouraged business creation

In many countries, including France before 2002, unemployed people lose their claims to unemployment benefits when they start a business. This discourages unemployed individuals to become entrepreneurs.

Consider for example an employee who loses her job after accumulating rights to twelve months of unemployment benefits. After three months of being unemployed, she decides to start her own business. She loses her unemployment benefits from day one of becoming an entrepreneur, even if she derives little income from the business during the first months of operation. Moreover, if she closes the business because it turns out to be unprofitable, she cannot claim the remaining nine months of unemployment benefits.

These unemployment insurance rules, though common, create a very strong disincentive for unemployed individuals to start new businesses.

When unemployment insurance helps business creation

France changed unemployment insurance rules in 2002. It allowed the unemployed-turned-entrepreneur to continue to collect her benefits so as to complement business income up to the full benefits she would have collected if she had remained unemployed. It does so until the business turns profitable or the person exhausts her rights to unemployment benefits. Moreover, if she closes her business within three years, she can claim her remaining benefits.

In theory, this new set of rules has two advantages. First, it provides downside protection to the entrepreneur. Many people with promising business ideas are held back from starting up because they cannot afford or are not willing to bear the risk of failing, such as people who have children, a mortgage, or other financial commitments. Providing entrepreneurs with a fallback option allows them to experiment with new ideas.

Providing entrepreneurs with a fallback option allows them to experiment with new ideas.

The second advantage of the reform is its potentially very low fiscal cost. If new businesses are profitable, little benefits will actually be paid out. The unemployment agency may even save money if the reform shortens unemployment spells.

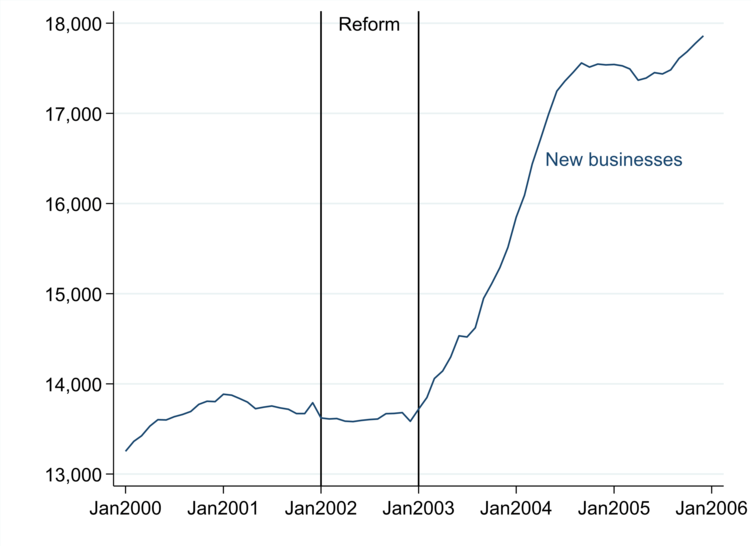

These theoretical advantages are confirmed by data on new business creation from the French Statistical Office. Total business creation increased by 25% after the reform, from 14,000 to 18,000 new businesses per month (see Fig. 1).

However, this increase is not sufficient to claim success because these additional 4,000 new businesses per month may be low quality ventures with no growth potential. For example, critics might argue that unemployed people do not usually make good entrepreneurs and that their businesses will fail more often than others, and will not create jobs in the long run.

Fig. 1: Monthly business creation. Source: Insee.

Businesses created while receiving unemployment insurance foster job creation

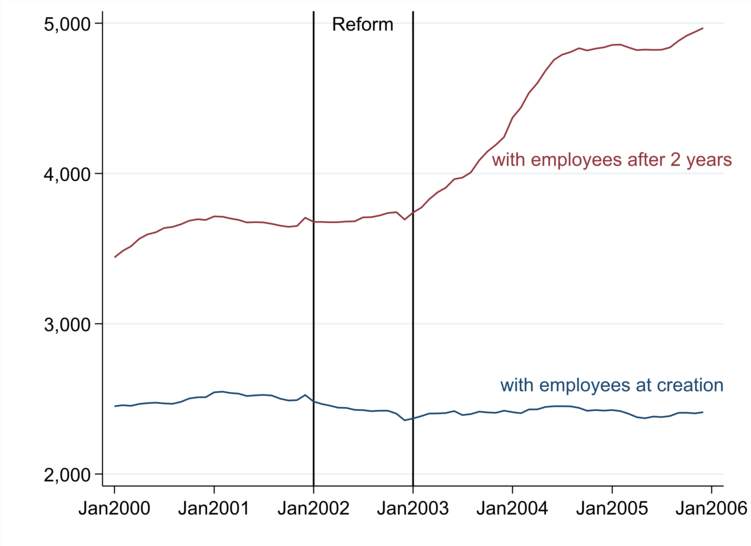

To dive into the job creation potential of new businesses, we distinguish businesses that create jobs (additional to the entrepreneur’s job) from businesses that do not create any. When we draw this distinction by counting jobs at the time of business creation, we find that the number of firms created with at least one employee is flat after the reform (blue line on Fig. 2). That is, none of the new monthly 4,000 businesses have employees beyond the entrepreneur herself.

Although it sounds disappointing, this finding is expected. Unemployed individuals are likely to lack financial capital and to start to experiment with business ideas at a small scale. The right way to test whether these new businesses are successful is not by counting jobs when the business is starting, but a little while thereafter.

We therefore repeat the same exercise by counting jobs two years after creation. The picture is now truly different. The number of new businesses with at least one employee after two years increases significantly after the reform, from about 3,500 to 5,000 per month (red line on Fig. 2).

Businesses created through the reform start small but a significant fraction of them eventually grow and create jobs.

It means that businesses created through the reform start small but a significant fraction of them eventually grow and create jobs.

We find similar results when we count the number of new firms with at least two or three employees.

We also find that these new firms are not more likely to fail and are not less likely to be profitable compared to firms started before the reform.

Fig. 2: New businesses with employees at creation (blue) and new businesses with employees two years after creation (red). Source: Insee.

A well-designed unemployment insurance is a low-risk help to experiment a new business

This policy experiment teaches us several important messages. Firstly, entrepreneurial experimentation is key. Many entrepreneurs start small, experiment with business ideas, test their taste and their ability for being entrepreneurs, and some of them eventually grow larger. Providing entrepreneurs with downside protection is therefore a powerful tool to foster business creation.

Secondly, the fiscal cost of providing entrepreneurs with downside protection needs not be high. The unemployment agency unfortunately does not release data allowing us to make a precise calculation of the fiscal cost of the reform. However, our estimates based on available data indicate that the fiscal cost has been low.

A key feature of the reform is that the government did not try to act as a venture capitalist by picking entrepreneurs or industries.

Last but not least, the reform highlights that policy design is key. A key feature of the reform is that the government did not try to act as a venture capitalist by picking entrepreneurs or industries. This is a desirable feature of the reform because governments usually make poor venture capitalists by lack of expertise and risk of political capture. Instead, the scheme was open to all unemployed individuals, and the data shows that it did not attract less able or less ambitious entrepreneurs.

Knowledge@HEC: Do you encourage the government to pursue this reformed unemployment insurance to stimulate the economy during the current crisis?

Our research highlights that it is important to keep this scheme alive, especially in a context of rising job destruction and rising uncertainty for entrepreneurs in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Well-designed unemployment insurance is an efficient way to combat both problems, helping unemployment people create jobs for themselves and for others, and fostering new business creation at the same time.