Crisis management, often associated with public relations, has a long history in the business world. Its founding is often attributed to Lee Ivy, the legendary creator of modern public relations. In 1913, John D. Rockefeller Jr., one of the richest and most hated public figures in the USA, needed protection. The crisis Rockefeller faced was the Ludlow Massacre, where forty miners and their families were killed during a labour strike at one of Rockefeller’s coalmines. Rockefeller, already a vilified public figure in the U.S.A., came under extreme pressure to repair his personal and corporate reputation.

Ivy Lee took charge of the crisis and began spreading positive stories about Rockefeller in the American press. A subsequent US Congressional investigation cast doubt on the objectivity of these stories concluding, “Perhaps a more dubious practice was the fact that his entire bulletin strategy was predicated on making it appear that the bulletins were published on behalf of the operators, not the Rockefellers.” In other words, Ivy created positive news stories supposedly sourced from coal mines owners but obscured that these were in fact written on behalf of Rockefeller. Even though Ivy was able to eventually convince Rockefeller that he should treat his miners better, the “fake news industry” was a direct result of this campaign.

Fast forwarding nearly one hundred years finds the practice of using fake news to change, guide, or reinforce public opinion alive and well. The HEC Paris students in the seminar were being equipped with modern tools necessary to manage crises on behalf of companies, their CEOs, and other public figures.

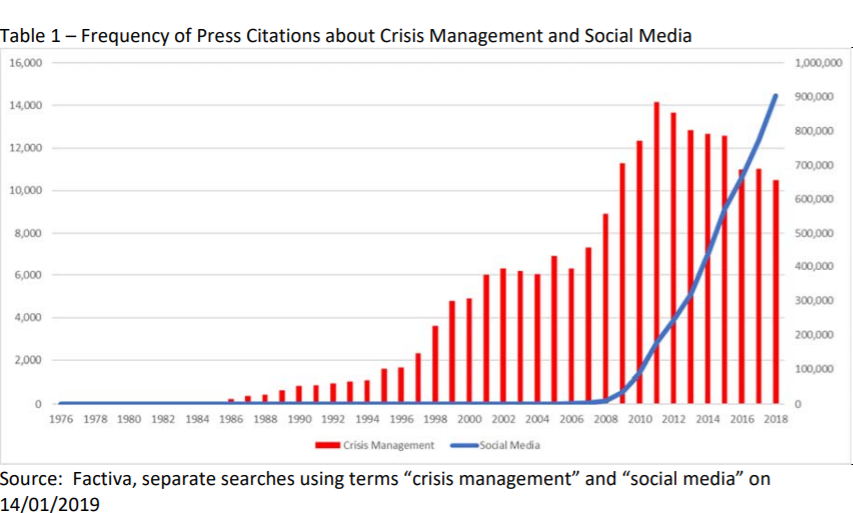

The rise of crisis management is displayed in Table 1 and there appears to be a strong correlation between the frequency of press citations about crisis management, the growth of the internet, and the development of social media sites.

The growth of interest in crisis management appears to correlate with popular awareness of the internet and the development of social media sites, which began in the mid to late 1990s but rapidly accelerated a decade later with social media sites such as Facebook.

Neither François nor Rouziès claim any relationship between the growth of crisis management and social media. However, before the internet, the development of powerful internet search engines, and the development of social media platforms, a corporate crisis must have been more difficult to sustain across news cycles. Crisis management practitioners like Ivy Lee and his 20th century colleagues did not have to contend with the easy distribution of bad publicity and continued availability of easily findable negative information about the transgressions of companies, their executives, or public figures.

Many newspapers were indexed but these indices were typically stored on thousands of microfiche films warehoused in libraries. Finding damning, reputation killing information was arduous work. The internet and social media sites make finding and distributing “bad press” simple.

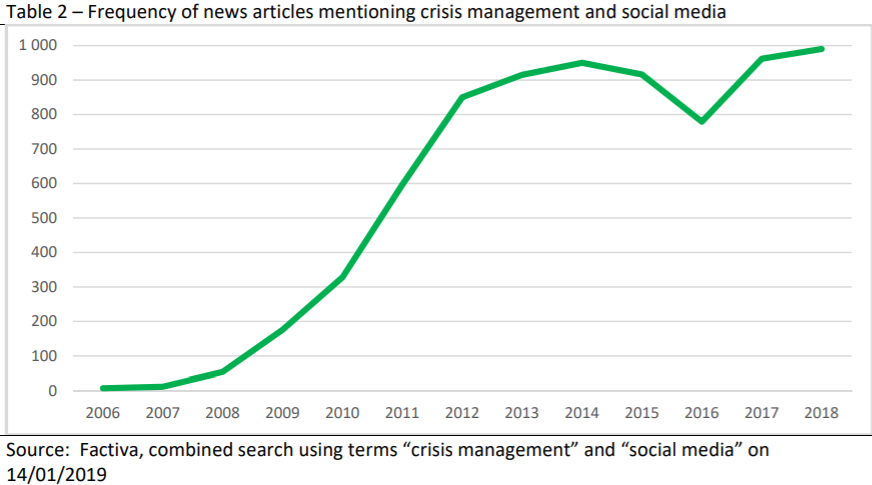

The new reality is displayed in Table 2. Reports mentioning both “crisis management” and “social media” in the world’s press went from zero in 2005 to nearly 1000 in 2018. It is clear that public relations professionals need to acquire new and more powerful tools to protect their clients.

Faced with the ease by which any mistake or deliberate act made by a company or person can now be amplified, François and Rouziès realized that public relations and marketing students would need new tools and skills to combat reputational attacks on their clients.

In 2005 François began offering the seminar designed to provide these tools and skills to HEC Paris students. Neither suspected that the simulation used in the seminar would escape the confines of HEC Paris’s classroom and enter into the real world of fake news.

Students enrolled in the seminar were divided into two teams. These teams created a fictional company, Laboratoires Berden, with a fictional CEO, Eric Dumonpierre. Berden was a pharmaceutical firm marketing Mutorex, a fictional by effective drug to treat obesity. Each generation of student teams contributed a “crisis” (e.g., child labour claims, an executive’s mysterious suicide, serious side effects of Mutorex, etc.) while the second team worked on Berden’s behalf to tamp down each manufactured crisis. The seminar ran for nine years at HEC Paris and was very popular among the students.

What surprised both François and Rouziès is that somehow the large universe of websites created within the closed sandbox of servers that powered this simulation leaked into the public realm. The fake company and the fake CEO started getting attention from the real press. Searches on the internet returned the name of Eric Dumonpierre based on his fake reputation as a champion of CSR. Job applicants started emailing CVs to Berden. The company received a complaint from a real pharmaceutical company concerning its unauthorized commercialization of Mutorex. Even now, four years after this seminar ended, a search of Laboratoires Berden, Eric Dumonpierre, and the other fictitious organizations created by the students, returns nearly 20,000 internet hits.

The lessons learned by this pedagogical experiment are discussed in the Harvard Business Review article that François and Rouziès published in July 2018. A key takeaway concerns reputation management and social media. Research shows that corporate and personal reputations are strongly linked to value creation. The difference nowadays is the speed at which reputations can be attacked in the current “fake news” environment.