While many may think creativity will be a key human capacity as work processes get increasingly automated, AI-applications get more creative as well: for example, AI-painted portraits sell at exorbitant prices, pop hits feature AI-generated music, and mainstream media ‘hire’ AI-journalists to publish thousands of articles a week. How workplace AI-application will impact creative processes, crucial for innovation and organizational development, is an important question that needs rigorous scientific attention.

What can research bring to the field of creativity with AI?

Research can help find ways to foster creative work and innovation augmented by the numerous AI-provided capacities. We need research that explains how we can create and adapt artificial agents and arrange working processes such that employees do not have to be defensive against AI and be more creative.

By now, we have learned that many people believe that artificial agents – these are, for instance, AI-run apps like Siri or Alexa, or social robots you may see at an airport - are not suited for creative work or work that requires diplomacy and judgement skills. So, normally people would not care much about AI trying to compose a symphony or write a novel as long as they believe that humans are creatively superior. But we also know that when AI is involved in creative work – for example, generating image suggestions, or even creating logotypes at a design studio, people often reject its results and evaluate them lower even if the AI objectively performs just as well as a human.

This is a problem because when employees believe that AI should not be creative and it turns out to be exactly that, they may feel threatened by it, fearing it might substitute them, and these feelings are normally not very conducive to creativity. In addition, when threatened, employees will try to protect themselves – after all, we want to feel that we, humans, the creative species, are unique. This hence may also hinder creative work.

How can your research help manage creative human-AI interactions?

Together with my advisor Professor Mathis Schulte, we investigate the differences in how people work on creative and non-creative tasks when they collaborate with AI, compete with it, or use results of its work as a benchmark for their own performance. We also investigate how these interactions are different from same situations in which a human counterpart is involved instead of an AI agent.

Creative interactions with AI is a nascent area of managerial knowledge, and we are excited to be making first contributions to it. We show, for instance, that people use the same psychological mechanisms in comparing themselves to AI agents, even when they believe these agents can’t really compete with people creatively. We also show that what we believe about ourselves and about AI matters, and while some beliefs can make employees work harder on creative tasks, other may demotivate them. Knowing what these configurations are will help managers set up collaborations such that AI is used to its full capacity, and people blossom in creative work.

We show, for instance, that people use the same psychological mechanisms in comparing themselves to AI agents, even when they believe these agents can’t really compete with people creatively.

So, what main differences do you find between human-human and human-AI creative interactions?

First of all, we saw that people did not take as much time to work on a creative task – that is, they were not as effortful - when they collaborated with an AI as when they collaborated with a colleague. This was not the case for a non-creative task, in which people worked on average for the same time both with an AI and a human collaborator. To illustrate, in one of our experiments, the creative task was to come up with recycling ideas for a medical mask (this task could be, for example, a challenge in an engineering competition, or a topic for an entertaining article, which was the setting in our experiment). The non-creative task was to find recycling-related words in a word matrix that needed to be tested as a game for publishing online.

People were not as effortful to work on a creative task when they collaborated with an AI as when they collaborated with a colleague.

We also found that an AI’s performance did not matter for such a decrease in effort. In a different experiment, we asked the participants to propose ideas on how to motivate their colleagues to move more or to eat better. We then showed them either a list of nonsense ideas (which really was a text generated by an algorithm!) or a list of sensible ideas. We told the participants that the list they see was either created by an AI or by someone else who also participated in the experiment. As a result, some people saw a nonsense list of ideas and thought it was proposed by an AI, and others thought that same list was suggested by a human. Regarding the list of sensible ideas, a third group saw a sensible list that was ostensibly AI-written, and the last group thought it was a human suggestion. Then, we again asked the participants to propose ideas on one of the topics. We found that no matter whether the ideas made sense or not, participants who looked at ideas that were introduced as suggested by other people took almost half a minute longer on the second task than those who thought the ideas were AI-generated.

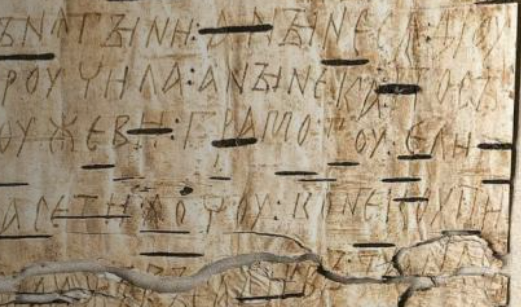

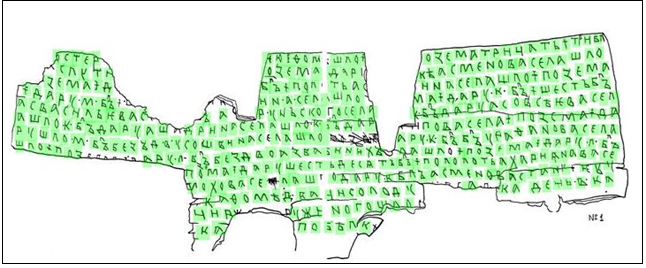

Interestingly, this was also the case in the non-creative task, in which participants looked for a specific character on an old-Russian birch bark, looked at the results of work of an AI or a human, and looked for another character again. Although we did not expect them to, participants who saw the results of AI’s work, both done well and failed, took less time to work on the task in the second round.

The results of these two experiments suggest that in many cases, especially when we think AI has no place in creative work, we might be less motivated to exert effort on it than we do when working together with another human.

In many cases, we might be less motivated to exert effort on creative work when there is AI participation, than we do when working together with another human.

So what are the conditions in which AI can motivate us try harder on a creative task?

This we tackled in a further experiment. In it, we again had participants think about creative ideas for the use of a medical mask or medical gloves. But, unlike in the first experiment, we first subtly made half of the participants remember that creativity is what makes humans unique, while the other half did not see such a reminder. We also told the participants that either an AI or a person came up either with many creative ideas, or with only a few. The results of these manipulations were astounding: while people who were reminded that creativity is a uniquely human trait and saw that AI came up with 20 ideas worked on average for almost full five minutes, those who were also reminded of creativity uniqueness but saw that it was a person that thought of 20 ideas took only 3.5 minutes to work on the task. We also saw that when high creative performance of AI was unexpected, people were much more threatened by that AI.

What are the implications of these findings for practice?

These findings have very important implications for practice: what should we tell employees about AI-applications that can be used in creative work to not have them disengage as they have nothing to prove against supposedly non-creative AI? How do we motivate them to perform creatively without scaring them with AI? These are the questions that I am looking forward to solving in my future work.

You’re using some unusual online services to conduct your research. Can you describe how you recruit your participants and why these services are so attractive?

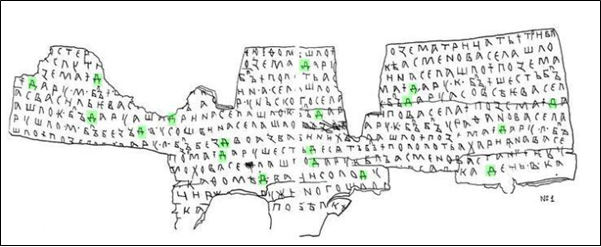

People who participated in these experiments were recruited either on Prolific, which is a rather popular British service for academic research, or on Yandex.Toloka, which is a Russian service for recruitment of individual workers on mini-tasks like data markup.

Using both platforms is a great advantage. First, I can test whether the effects I hypothesize are universal across different cultures and nationalities. Second, as specialized platforms have recently been criticized for data quality, people that I recruit at Yandex.Toloka, which is primarily used by businesses for crowdsourcing, are naïve to experimental studies and, as the majority of these tasks are quite mechanical and dull, they are intrinsically motivated to participate in my experiments – I have received quite a few messages from participants saying that they enjoyed the “task” and would be willing to do it again. Although, unfortunately for these participants, that will not be possible to not compromise the integrity of the research, I think it says much about how people are unlikely to sabotage participation.

I can test whether the effects I hypothesize are universal across different cultures and nationalities.

Finally, Yandex.Toloka offers a great gender balance in the sample (51% of participants I randomly recruit there are women), people come from different walks of life and mostly have had quite a lot of working experience – their average age is almost 36 years. These factors make the use of both services a great strength of my research design, and I thank GREGHEC Laboratory for enabling me to use them by providing research support in the form of funding that got me almost 1200 participants.