It all started when I was a Ph.D. student at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh. As I was approaching the end of my first year, my Department Head told me that my introductory stipend was nearing its end and would not be continued in my second year. Either I would have to find a professor who was willing to pay my tuition and living expenses, or I would have to raise money to cover it myself. At that time, the estimate for Carnegie Mellon tuition and costs was roughly $32,000 per year. Back home, in Sweden, my parents were poor farmers without enough money to visit me, let alone for anything else. However, finding a professor to fund my education meant pursuing a thesis topic on a project that had already been funded. Although there were several potential projects available, none of them were particularly interesting to me—I wanted to do my own thing. I decided to somehow find the funding for my three remaining years myself. And I wanted to be with my girlfriend who was back in Sweden; so, I packed up my only suitcase and returned home.

A month before finishing my first-year final exams, I sent a letter to about 20 large Swedish companies—Volvo, SKF, ABB, among others—stating I would be available to do some consulting work should there be a need. It was quite presumptuous, and, indeed, I only received one reply. But Skandia Insurance Company did invite me to its headquarters in Stockholm to work on a project. Meanwhile, I was also able to secure a part-time job as a project manager for the upcoming year at a research institute affiliated with Chalmers University in Göteborg. In addition, over the course of the same year, I wrote about 20 applications and finally obtained two scholarships for my continued studies in Pittsburgh.

In retrospect, my year in Sweden was definitely a success from a venturing perspective. I had had a steady job that paid the bills, and I did approximately 100 days of consulting for Skandia, working on several interesting projects in Stockholm whilst touring their branches across Europe. I learned a myriad of new things about business, but the main reason for me becoming an entrepreneur was to make money. Indeed, the money I earned from the consulting went straight to the bank and it lasted three years before being completely depleted, primarily due to high tuition fees at Carnegie Mellon. Some may say that this was “necessity” entrepreneurship—after all, I became an entrepreneur strictly to fund my Ph.D. studies. But it was relatively riskless, and I certainly was not destitute (1). However, consulting was not for me. By the end of my year in Sweden, I was stressed and nursing a stomach ulcer. It was time to go back to Pittsburgh.

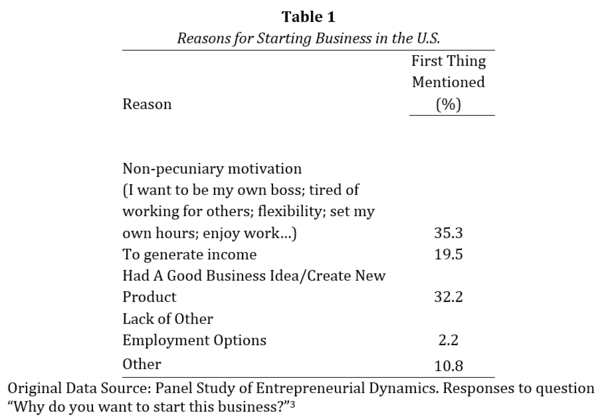

Now, let us consider for a moment in more general terms the reasons why a person like you may start a business. This information may help calibrate your own decision to become an entrepreneur. Table 1 reports the responses of “nascent” entrepreneurs in the U.S. when asked: “Why do you want to start this business?” (2) Rather surprisingly, perhaps, is that among the five categories that comprise the most important reasons, making money, is not one of them. Only one-fifth of entrepreneurs report that they started a business to make money. Instead, most cite non-monetary reasons. For example, survey participants most frequently respond “To be my own boss”, or “I am tired of working for the man”, or “I want to manage my own time!”

If you want to start a business to be your own boss, you have plenty of company.

In fact, an astounding 71% of all employees in the U.S. and 42% of all French employees want to become entrepreneurs. Why so many?

It turns out that people are mightily dissatisfied with being employees

Table 1. shows how dissatisfied Americans are with being an employee or being self-employed. The fraction that are either very or a little dissatisfied is twice as high among employees as it is among entrepreneurs.

|

Employees |

Self-employed |

|

|

Very dissatisfied |

3.8% |

2.0% |

|

A little dissatisfied |

10.3% |

5.8% |

|

Moderately satisfied |

39.9% |

29.8% |

|

Very satisfied |

45.9% |

62.5% |

Table 2. Job satisfaction among self-employed and wage workers in the U.S. (4)

Why so happy with being an entrepreneur? Partly it is because self-employed people report that their work provides more autonomy, flexibility, and skill utilization. But while self-employed people are more satisfied than wage workers with their jobs and, in general, with their life, the self-employed also report that they work longer hours, feel greater pressure at work, are in poorer health, come home from work exhausted; that their job limits their family time; that they felt too tired after work to enjoy the things they would like to do in the home; that their partner/family gets fed up with the pressure of their job; and that they had lost sleep over worry, felt unhappy and depressed, were constantly under strain, and worked under a great deal of pressure.

Now, after reading the story of my first venture, and looking at general evidence of why people become entrepreneurs and how they feel about being an entrepreneur, please take a moment to ask yourself these three questions before you consider becoming an entrepreneur: Will I enjoy it, given all the hardship, the late hours, and the stress? Would I be ok to lose all the money I put in this venture, including money from my friends and family who I will ask for investment? Will I be able to bounce back by getting a regular job if I fail? If you answer ‘no’ to all of these questions, then you should definitely not become an entrepreneur. If all of your answers are ‘yes’, then you could do it, but understand that answering in the affirmative will not make you more successful. If one or two answers are no, you are in a tricky spot, and it would be a really bad idea for me to advise you what to do next.

Self-help questionnaire for those considering to become an entrepreneur

If you answer ‘no’ to all three questions you should definitely not be an entrepreneur. If you answer yes to all three questions you will have fun, and you will not, hopefully, come out hurting too much. If you answer no to at least one, think hard about doing something else equally thrilling but less costly, such as hang-gliding or parachuting.

|

Yes |

No |

|

|

Will I enjoy it, despite working longer hours, feeling stressed, sleeping poorly, and not having time for anything else? |

||

|

Would I be ok to lose all the money I put in this venture, including the money from my friends and family who I will ask to help me out? |

||

|

Will I get able to bounce back by getting a regular job if I fail? |