Men are hopeless at caring for infants. But they’re aces when it comes to space exploration and athletic exploits. Women, on the other hand, are good at making sandwiches, doing the laundry and sitting on park benches next to baby carriages.

Or at least that’s what’s implied in two ads banned in the U.K. in 2019 for gender stereotyping. The ads, for Philadelphia Cream Cheese and the VW Golf, were the first to be found to have violated the then-recent ban on “harmful gender stereotypes” enacted by the country’s Advertising Standards Authority.

Gender bias may be cued, more or less consciously, by marketing initiatives. The U.K. ban, similar to ones in other countries, forces companies to reflect on their own explicit or implicit biases. Our research shows that consumer bias makes brands identified as “female” less appealing for male shoppers. But we also prove that marketers have tools to change the stereotypical narrative and rise above outmoded ideas.

Marlboro Man vs. Mrs. Butterworth

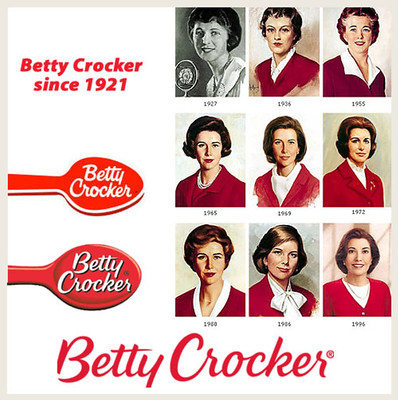

Our studies of gendered brand representations (such as the Marlboro Man or Mrs. Butterworth) support previous research that shows that consumers tend to favor male brand names over female. Specifically, we find that men devalue brands with female names or representations (such as logos or spokespeople), whereas women do not. Conversely, men have a stronger connection with brands with a masculine representation, though women do not show a marked preference.

Domy Towarowe "Centrum" by Cezary Piwowarsk

Men tend to exhibit a stronger brand connection with “masculine” brands when they have a more conservative attitude toward societal roles — when they view women as suited for domestic roles and men for more active roles in competitive markets.

Men tend to exhibit a stronger brand connection with “masculine” brands when they have a more conservative attitude toward societal roles.

In our work, we present strategies to mitigate the gender bias by men against female brands so that male and female brands can eventually be valued equally within the marketplace. In doing so, we provide tools for the many 21st-century organizations that are retreating from archaic narratives about gender and race.

Green tea and Monopoly experiments confirm sex-role bias

We conducted three online experiments using three gender-neutral products: green tea, the Monopoly board game and Pringles chips. In the first, we randomly assigned subjects one of three tea brands: one that was gender-neutral (Harney Premium Green Tea), another that had a male brand name (Harney & Sons Premium Green Tea) and a third that had a female brand name (Harney & Daughters Premium Green Tea).

As we expected, brands with male or neutral names resulted in higher purchase intentions. Further, men devalued the female brand, while women showed no preference.

In a second experiment, participants were presented with the Monopoly board game logo, Mr. Rich Uncle Pennybags, or a redesigned female logo, Ms. Rich Aunt Pennybags.

The results confirmed those of the first experiment. Men were more likely to devalue the game with a female representation, while women showed no preference. Men felt a stronger brand connection to the game with a male representation.

Language matters

Finally, in our Pringles experiment, we studied whether female brands could benefit from “agentic positioning,” that is, whether assertive, confident language paired with a female brand would mitigate men’s negative bias.

We told the all-male participants that Pringles had a new logo, and they were presented with either a male or female version of the logo. The participants were either given no accompanying text, an assertive brand statement (the brand is “driven to be an assertive market player”) or an expressive brand statement (the brand is “driven by consumer well-being”).

The results reproduced those of the first two experiments, but also found that men’s decreased intentions to purchase female brands can be influenced with agentic, “male” positioning. When assertive language was used, men were actually more likely to purchase brands with female representations than those with male representations. The communal, “feminine” text did not influence purchase intentions.

A way forward

Our research breaks down what happens when brand names have male or female representations. If a brand is given human qualities (such as a first and/or last name), consumers will naturally form humanlike relationships with them. Unfortunately, that also includes the gender bias that often accompanies human relations. Yet, our research also points out some ways of decreasing this bias.

Instead of merely capitulating to gender bias, our research found that the use of assertive language with a female brand name nullified the bias.

Instead of merely capitulating to gender bias, as other researchers suggest —recommending the use of male brand representations over female — our research found that the use of assertive language with a female brand name nullified the bias.

We feel it is time to implement new strategies in marketing in order to reduce the disadvantage that female-identified brands experience in the marketplace. Instead of contributing to the dominant discourses of masculinity, we argue it is instead fruitful to try to change it.