Advertising is a fundamental part of modern commercial activity, enabling companies to influence how consumers think, feel, and act about brands. But this rarely translates into immediate sales.

An advertisement for a new drink may make consumers aware that the product exists, but that doesn't mean they will want to buy it. Any effect advertising does have on sales is usually slow to appear, and other factors, including actions taken by competing brands, may mask the effect. Since the early days of marketing management, researchers have known that advertising primarily influences customers' mindsets.

Most experts regard measures of consumer mindset, so-called mindset metrics, as more direct and reliable measures of the effectiveness of advertising. They include the awareness that the brand exists, the likelihood that it comes to mind when one thinks about the product category, the recollection of a previous advertising campaign, the affect or feelings towards the brand, and the intent to purchase the product.

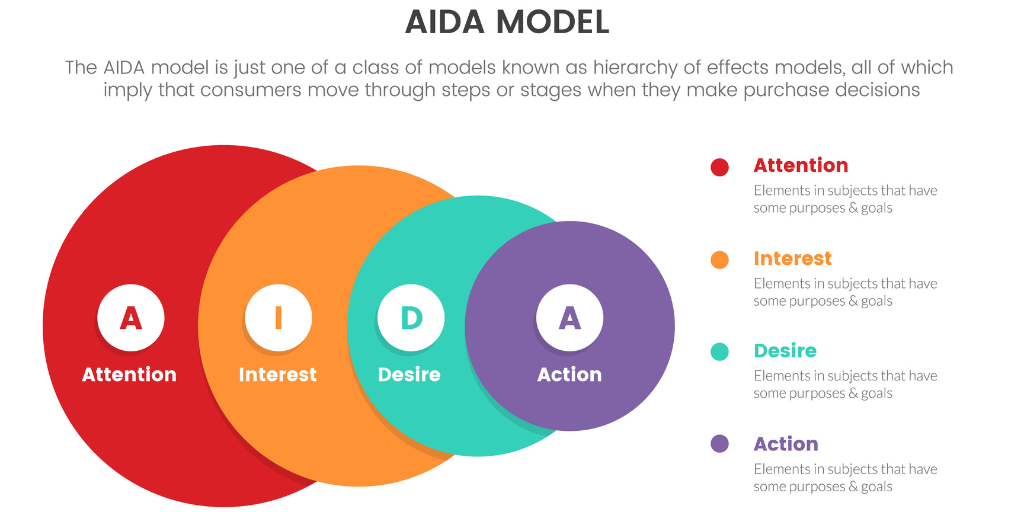

Many experts believe the influence of advertising on consumer mindsets follows discrete steps: there is a fixed sequence of mindset effects, with one effect leading to the next, eventually leading to buying behavior. This particular order of effects is called the 'hierarchy-of-effects' framework and is taught in most, if not all, communications and marketing courses. A version of this framework, AIDA (awareness, interest, desire, action), was described as long ago as 1900. Yet, despite its longevity as a concept, there is almost no empirical evidence of a hierarchy of effects.

To our knowledge, we are the first to validate the hierarchy-of-effects framework using data on the complete sequence from advertising to mindset to sales.

Yes, there is a hierarchical sequence of advertising effects on consumers

In this study, we wanted to ascertain if there is a hierarchical sequence of effects in advertising. We also wanted to know if there are specific sequences for different brands and categories, and we wanted to establish which mindset factors are most important in driving sales.

To obtain answers, we obtained monthly data on advertising expenses, sales, and mindset metrics for 178 fast-moving consumer goods brands in 18 categories over seven years. In the past, researchers have used a variety of different mindset metrics, defining and understanding them in different ways. We analyzed three metrics, which we refer to as cognition, affect, and experience. Here, the cognition metric is a measure of how aware the consumer is of the brand. The affect metric represents the consumer's reported level of liking of the brand. Finally, the experience metric represents the extent to which advertising has reinforced the consumer's prior positive experience with a brand, thus impacting the likelihood that they will purchase it again.

We worked at an aggregate level and did not examine the content of specific advertising campaigns. Knowing how much a brand spent on advertising, period by period, we were able to assess the effectiveness of that advertising through its effect on consumer mindset.

The difference between advertising makeup and detergent

Some researchers have proposed that the sequence of effects on consumers' mindset should be adapted to different products and different situations. In contrast, some propose that a fixed and universal sequence would hold for all products. And still others have rejected the hierarchy-of-effects framework altogether, arguing that advertising influences all mindset metrics simultaneously.

Our study showed, plainly and for the first time, that for most brands, advertising elicits a clear and repeatable sequence of effects on mindset metrics. Further, there are different sequences for different brands and different kinds of products. For each brand, we were able to determine a dominant sequence.

The 'affect -> cognition -> experience' is the most common sequence, even more prevalent for utilitarian, everyday products, as opposed to hedonic products.

We were able to work out some general patterns. Overall, 'affect -> cognition -> experience' (ACE) is the most common sequence, occurring across about half of the brands. The ACE sequence is even more prevalent for utilitarian, everyday products (those that are typically chosen logically and objectively, based on considerations about how well they work) as opposed to hedonic products (such as soft drinks, yoghurts, and makeup, where choice is based on feeling, looks, taste or smell, or on the extent to which they express one’s personality).

The ACE sequence is also more prevalent for non-differentiated brands as opposed to ones with more unique selling points. Non-differentiated brands are those not aimed at specialized uses within a category. A non-differentiated laundry detergent, for example, would be marketed for use with all kinds of laundry. A differentiated laundry detergent might be marketed as specifically designed for delicate items. A non-differentiated shampoo brand would be aimed at general use for all types of hair, while a differentiated shampoo brand might be marketed as providing dandruff control.

Our results also show that consumer awareness of a product is most responsive to advertising, while the last mindset metric in the sequence, usually experience, is the most important in driving sales. Long-term effects of advertising were observed on both mindset and sales figures. More generally, we showed that the assessment of mindset metrics is a reliable means of evaluating the effects of advertising.

Designing advertising campaigns more effectively

Our work has clear implications in terms of the use and interpretation of mindset metrics by marketing managers, whose central tasks include the administration and optimization of advertising budgets. They can use our findings to inform the design of advertising and communication campaigns to differentially influence the sequence of mindset effects for a brand.

In academia, as already mentioned, the hierarchy-of-effects framework is well established and widely taught. It is also used by marketing practitioners to interpret the compiled mindset data on their brands, allowing them to assess the effectiveness of campaigns and brand performance and make corrections if needed. However, until now, research results have been somewhat contradictory, and experts have not been able to provide clear guidance, nor have marketing textbooks provided specific advice, for managerial decision-making.