You study palace construction in early-modern Rome. Why did you choose this topic?

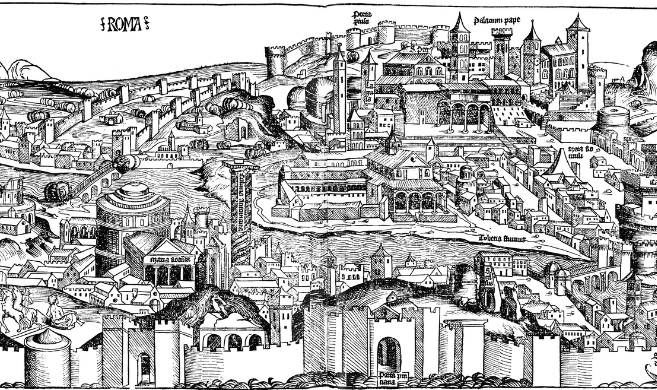

Rome, in the 14th-15th centuries, is in ruins. Contemporaries describe a “cadaver.” “A great stable for sheep.” Artists depict a grieving widow, clad in black, pleading with passersby.

Then comes an economic revolution: an era of palace building dawns in Rome. A city suffering from dereliction transforms into a flourishing metropolis.

So, why Rome? Why the Renaissance? I wanted to understand how this recovery – an economic boom of miraculous proportion – could happen.

I wanted to understand how this recovery could happen.

There are many possible explanations. Among the most plausible is the return of the papacy to Rome following a seven-decade-long sojourn in Avignon (1309-1377). Rome is a bit like a company town. The absence of the papacy deprives the city of economic activity, so when the papacy comes back, so, too, does the economy.

But this answer is not entirely satisfying: the papacy returns in the late 14th century; the recovery, however, only begins towards the end of the 15th century.

Now, there is also a papal bull (a piece of executive papal legislation) in 1480, which reforms inheritance laws for high-ranking ecclesiastical officials. It becomes easier for these prelates to leave property to heirs. Shortly thereafter, there is an increase in real estate investment.

I first discovered mention of this papal bull in a book by Kenneth Bartlett ("A Short History of the Italian Renaissance"), who suggested that there may be a connection between the reform and the restoration of Rome. While the conjecture has been echoed in a number of historians' works, it had never – to the best of my knowledge – been tested. Since then, I've had the opportunity to discuss these ideas with a number of economists and historians, and, though I, unfortunately, cannot possibly thank here everyone from whose wisdom I benefitted along the way, I would like to say that this project would not have been possible without the support of Aloysius Siow, Thomas and Elizabeth Cohen, and Kenneth Bartlett.

In short, this project asks: Could one change in inheritance laws really be responsible for the era of palace-building in Rome? And, if so, how?

It felt like a real mystery. What could be more exciting than trying to solve a centuries-old puzzle?

Can you explain this inheritance reform?

Before 1480, churchmen effectively faced a 100% tax rate on inheritance: clerical vows of celibacy precluded them from having an heir. The 1480 papal bull, without altering canon law, allows an heir to be appointed. The de facto tax on inheritance for these churchmen therefore falls to the 0%-rate faced by their lay counterparts.

This is a serious change. If you are a cardinal, you can now leave everything you own to your nephew. Maybe even to your illegitimate son. Your economic choices have value and consequences beyond your death; your decisions can advantage your family for generations to come. The incentives are completely different. Real estate investment is suddenly desirable.

What connections did you find between this reform, and the construction of palaces in Rome?

In the paper, I establish that the papal bull does have a positive causal effect on palace-construction in Rome. This is very much an empirical work: I use several sources – including maps and archivists’ accounts, complemented by a manual data-collection effort – to compile a novel dataset to test my hypotheses in a statistically-rigorous way. It's a great joy to bring the tools of finance and economics to historical questions.

It's a great joy to bring the tools of finance and economics to historical questions.

In particular, to examine the direct effects of the papal bull, I compare differences in investment rates by patron type. I find that high-ranking ecclesiastical officials (who benefit directly from the papal bull) invest much more in real estate following the reform than a control group of laymen.

But this is only part of the story. Surely people remembered the devastation wrought by the papacy’s prolonged absence. Surely they worried that the pope could leave again, as suddenly as he had before. The Western Schism (1378-1417) – a period of political turmoil with several simultaneously-reigning popes – and subsequent years of instability did little to assuage such fears.

Nearly every facet of the Roman economy was dependent on the papacy; so, even the most dramatic of reforms would have been futile if people had not believed that the papacy really was staying in Rome long-term. The volatility of papal politics made the city a risky choice for investment, especially where illiquid real estate was concerned.

Indeed, though laymen were not affected by the constraints on inheritance that churchmen faced, they still did not invest in real estate pre-1480. For as long as they feared the departure of the papacy, there was just no future for them to invest in.

I think there is good reason to believe that the papal bull solves this problem, too.

Can you explain why the papal bull reversed the real estate investment trends in Rome?

Cardinals elect popes. Once they are invested in the city – thanks to this reform – their financial future and the economic well-being of Rome are inextricably linked. The College of Cardinals would never elect a pope willing to leave Rome, devaluing their own property. The papacy meaningfully commits to staying in Rome. This turns out to be a promise good enough for all patrons. So, even the laity benefits from this reform, albeit indirectly.

Consistent with this mechanism, I find that, post-1480, all investors begin to favor projects that are longer, more ambitious, or that otherwise incur more risk. Rome becomes a city with a more certain future, and hence with opportunities for profitable long-term investment.

The story I tell in this paper might be relevant to how we think about public policy, incentives, powerful stakeholders, investment, and even urban renewal.

How can understanding this historical phenomenon help us better understand the present and apprehend the future, and hence contribute to society?

The Renaissance was an amazing period. So much about the way we think about the world today – in terms of culture, politics, philosophy, economics – can be traced back to early-modern times. I think it is hard to understand the present without knowing about the past in general, and perhaps nearly impossible without the Renaissance in particular.

An economy in decline; a city in ruins; political intrigue; crisis and turmoil. This is not the mise-en-scène of a historical melodrama. This is still very much our world. There's a lot we can learn from it.

I would like to believe that the story I tell in this paper might be relevant to how we think about public policy, incentives, powerful stakeholders, investment, and even urban renewal. I hope that knowledge of the past can guide decisions of the future. But I do not think this work says – or should say – anything about a particular policy agenda today. That is where the story I tell stops, and the real world and the work of policy-makers begins.