From a theoretical point of view, there are two views on the impact of dividend taxation on the economy. The first is associated with neoclassical economic theory and inspires liberal political currents. It believes that lower taxes reduce the cost of financing for companies, as they have to compensate their shareholders less for these taxes. This has the effect of increasing corporate investment and, as a result, productivity, profits and, in the long run, dividends. An alternative view postulates that companies finance new investments by drawing on their reserves. A tax cut should therefore not affect corporate investment and productivity.

The Swiss case

The Swiss tax reform of 2011 provides an ideal framework for studying the impact of a dividend tax cut and testing these two competing theories. Let's take a step back in time. On February 24, 2008, the Swiss people accepted a corporate tax reform by a narrow majority. This package of measures was mainly aimed at reducing the tax burden on Swiss SMEs to facilitate their development and employment. In this context, the reform introduced the capital contribution principle, which allows the owner of a company to withdraw the capital provided to the company without being taxed.

When the reform came into force on January 1, 2011, an unforeseen element, which had never been discussed before the popular vote, appeared in the circular issued by the Federal Tax Administration. This circular explicitly allowed dividends to be paid from reserves from capital contributions. This new type of dividend was therefore completely tax-free. Thus, companies that had been able to obtain recognition of the constitution of such reserves since 1997 (mainly acquired through capital increases) were able to pay tax-free dividends to their shareholders. Since 2011, more than 140 Swiss listed companies have made use of this system. Our estimates indicate that an average of 10 billion Swiss francs in dividends net of tax has been paid out each year since 2011 (see Figure 1) and that these companies had, on average, reserves to pay seven years of untaxed dividends.

Figure 1: Evolution of total dividend payments (in CHF billion)

The introduction of the 2011 reform makes it possible to assess the impact of dividend taxation on corporate behaviour accurately. Indeed, we can consider that the possibility of paying a tax-free dividend was determined in a quasi-random way since it was impossible to anticipate the introduction of such a law and to build up reserves in anticipation of it. It is, therefore, possible to compare the behaviour of firms with reserves from capital contributions (RCC) with those that do not have any and that constitute a control group (without RCC). Since the business environment is the same for firms with and without RCC, any change in behaviour can be causally attributed to the tax cut.

No effect on the real economy

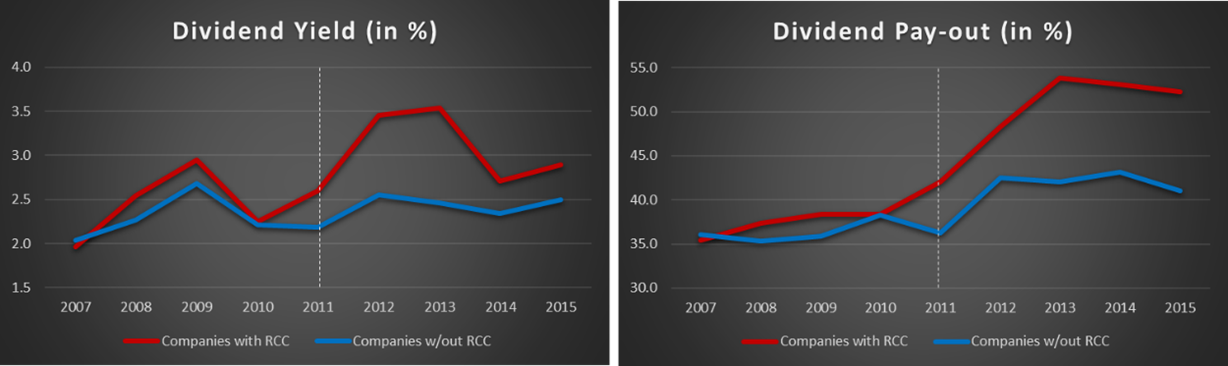

In a recently published study1, we analysed the behaviour of Swiss companies around the 2011 reform. In doing so, we were able to answer various open questions about the effect of dividend taxation. Our study shows that companies massively increase their dividends following the abolition of taxation (see Figure 2). Indeed, the average dividend yield and the average pay-out ratio have increased by about 30%, and the proportion of firms paying dividends has increased by 10%. The variations observed indicate that companies tend to retain too large a fraction of their resources within the company instead of redistributing them to their shareholders in the presence of taxes.

Our study shows that companies massively increased their dividends following the abolition of taxation.

Figure 2: Evolution of dividend payments

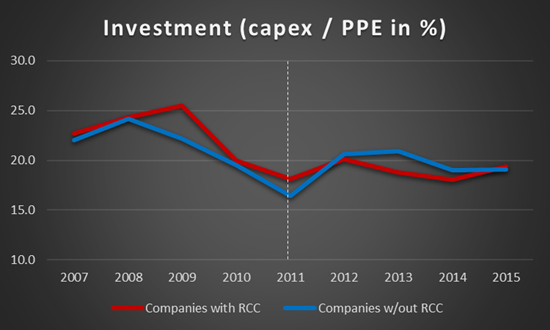

Following the announcement of tax-free dividend payments, companies' share prices affected by the reform increased by an average of 2.4%. This indicates that the removal of the tax has generated an increase in the valuation of companies. As for the real effects, we find that investments remain stable after the reform for both categories of firms (see Figure 3). This suggests that firms are relatively insensitive to the dividend tax rate and use their reserves to finance new investments.

Similarly, the number of employees and the wage levels have not been affected by the reform. Overall, our results clearly indicate that a reduction in dividend taxation has no real effect on the economy. Consequently, our study challenges the neoclassic view that any increase in dividend taxation weakens economic growth by reducing investment. Instead, our results show that a decrease in dividend taxation has a significant effect on the amount of dividends paid and the valuation of firms.

Investment, number of employees and wages: none of them has been affected by the reform.

Figure 3: Evolution of investment