Why are you warning tech workers against bubbles?

Inspired by exciting developments in new technologies and the high salaries offered in tech firms, many graduates are attracted by jobs in the tech sector. But when examining the long-term prospects, the current choice of many young talents to join the tech sector may actually be a risky bet. When looking at the long-term earnings of workers who started their career during the last tech boom in the late 1990s, we found that they ended up earning less than workers who started careers outside of ICT.

But wouldn't individuals starting in the booming tech sector acquire valuable skills – and be well paid for them?

The optimistic view is that individuals starting in a booming tech sector are exposed to new technologies, allowing them to acquire valuable skills and making them more productive in the long term. Even if the tech bubble bursts, so the argument goes, workers can redeploy these skills in other firms and sectors. But our findings seem to support the opposite view; i.e. that workers starting in a booming tech sector are at risk of acquiring human capital early in their career that will rapidly depreciate. As technological change accelerates during tech booms, workers who joined the tech bubble will be left behind.

As technological change accelerates during tech booms, workers who joined the tech bubble will be left behind.

How does “left behind” translate in terms of earnings?

We use linked employer-employee administrative data from France to study the long-term earnings of French high-skilled workers who started their career during the late 1990s ICT boom. The results point to long-term wage discount with high-skilled workers who started in the booming tech sector ending up earning almost 7% less than workers who started careers outside of ICT.

What exactly happened to careers and wages during the tech boom?

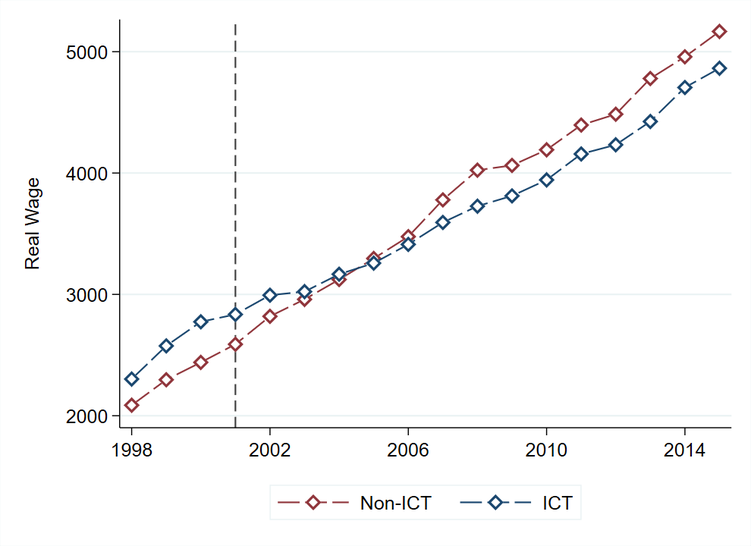

To study the impact of starting one's career in the booming sector tech, we zoomed in on the dot-com boom cohort of high-skilled workers who took their first job between 1998 and 2001. We compared the wage dynamics of those workers who started in the ICT sector to that of similar workers who starting in a different sector. As shown in Figure 1, and consistent with the boom creating a shortage of talents, high-skilled workers starting in the booming ICT sector earned on average 5% higher entry wages than workers starting in other sectors. As time went by, however, the wage difference between the two groups shrank and the two curves crossed in 2005. Stunningly, the difference kept widening such that by 2015, high-skilled workers who started in the booming ICT sector ended up earning almost 7% less than workers who started outside ICT. Overall, a career start in ICT is associated with 11 percentage points lower wage growth in the subsequent 15 years.

So the average pay is lower. But couldn't it simply mask the fact that there are winners and losers? After all, not all tech firms become success stories like Amazon.

One might indeed suspect that the long-term wage discount just boils down to the fact that weaker firms brought the average down. One might also wonder whether French tech firms are not low-quality firms altogether. Since our employee data can be linked with firms' tax filings, we were able to test these hypotheses. We found wage discounts of similar magnitude for workers starting in high-growth tech firms and for those in low-growth firms. We also found a similar discount for workers starting in the French offices of US tech companies and for those starting in French tech firms. The wage discount is therefore not a low-quality firm or a French firm phenomenon. In fact, we show an even more striking result: the wage discount is not explained by the fact that job losses increase in the ICT sector after the bust. Even workers who never lose their job experience the long-term wage discount.

The wage discount is therefore not a low-quality firm or a French firm phenomenon.

One might also think that the tech bubble created losers and winners among workers joining the bubble, such that the average wage discount actually masks a small probability of very positive outcomes. This is not the case. The entire distribution of earnings growth distribution of workers starting in the booming ICT sector is shifted to the left. The wage growth discount at the 90th percentile is similar to that at the 10th or 50th percentile.

Could there have been a selection effect, with the booming sector attracting less-than-productive individuals?

One might believe that the wage discount arises because workers attracted to the booming tech sector were of low intrinsic productivity, maybe because individuals pulled by fads are on average worse workers. Their low productivity would have been masked during the boom and became apparent when the boom ended and wages started to reflect workers' productivity more accurately. We tested this hypothesis by studying the cohort of high-skilled workers who started their career just before the boom, between 1994 and 1996. The idea is that these workers' career choices were not influenced by the bubble, which had not started yet, but those who started in ICT were subsequently exposed to the boom. Our results show that the wage dynamics of these workers is very similar to those of boom cohort workers. They benefit from a positive wage premium during the boom, followed by a long-term reversal, ending up in 2015 with wages 7% below that of entrants in other sectors. So the discount does not reflect a selection effect.

The bubble burst several years ago. What has been happening to wages in the tech sector since then?

The wage discount seems to contradict the notion that labour demand in ICT has been rising since the mid-2000s. This paradox is explained by the fact that the wage discount we uncover only applies to the boom cohort. When we replicate our analysis on the post-boom cohort of workers who started their career between 2003 and 2005, we find a completely different pattern. High-skilled workers starting in ICT after the boom face slightly lower entry wages than entrants in other sectors, but they catch up over time such that by 2015 there is no significant difference between the two groups.

So, what explains this long-term wage discount?

Our leading hypothesis is that human capital accumulated by high-skilled workers in the booming tech sector depreciates faster than usual because of accelerating technological change. As skills acquired during the boom become obsolete, workers who started in the booming tech sector experience poor long-term wage growth. A fact that is consistent with skill obsolescence is that, when we distinguish between high-skilled individuals holding a STEM (science, tech, engineering, maths) occupation and those holding a management/business occupation, we find that only the STEM workers experience the long-term wage discount, whereas business people are immunised against it. This is evidence that the discount has to do with technical skills, consistent with the obsolescence explanation.

As skills acquired during the boom become obsolete, workers who started in the booming tech sector experience poor long-term wage growth.

So your conclusion is that bubbles are bad news?

Bubbles in low-tech sectors such as housing have been shown to reduce educational attainment as individuals drop out of school to work in the bubbly sector, reducing long-term productivity. The hopes are that high-tech bubbles are different, if starting one's career in a booming tech sector fosters human capital accumulation. Unfortunately, evidence from the last tech boom is not consistent with such a bright view. Human capital accumulated during the tech boom turned out to have low long-term value. This is not to say that the tech boom did not increase aggregate productivity, but the talented individuals who contributed to the boom are not the ones who benefited from it.