Craig Anderson, you indicate that the study of awe is important in the context of CSR issues like greenhouse gas emissions, water conservation donations, waste reduction and so on. Could you tell us why?

Sure. Awe is an example of what we call a self-transcendent emotion, in contrast with emotions like anxiety or self-pity, where we focus on ourselves and our problems. With self-transcendent emotions, our attention turns away from ourselves and our egotistical concerns and we pay attention more to the others around us and what their needs are. Indeed, we find evidence that awe promotes prosocial behavior. And in our research, we extend that emotion to the environment, examining how awe might make people be more likely to do things that help the environment.

With self-transcendent emotions, our attention turns away from ourselves and we pay attention more to the others around us.

Craig Anderson opens his workshop on awe with an awe-inspiring visit to the Sainte Chapelle in Paris.

In the paper you co-publish in the American journal Affective Science, "Culture and Awe: Understanding Awe as a Mixed Emotion", you say that awe is a mixed emotion. Your research here suggests that awe evokes both positive and negative feelings, with its exact nature shaped by cultural backgrounds, and you and your six co-signatories explore this duality, focusing on how awe is experienced in the United States and China. Why choose those two cultural entities, China and the United States?

In cultural and psychological work, it is common for researchers to make Western versus Eastern comparisons. There are a lot of clearcut ways these societies are structured differently, how individuals think of their place in society that are different. One of the reasons is what's called dialectical thinking. Chinese people tend to be able to consider opposites in their minds at the same time. So, instead of black or white, maybe shades of gray. And as an American myself, I think it's fair to say that Americans are more black or white thinkers, they're less likely to be comfortable holding two opposite thoughts in their mind simultaneously. And this notion is reflected in our findings.

So, when we showed participants the exact same awe-inspiring stimulus, a video of vast mountain peaks, for example, Americans had almost an exclusively positive reaction to that. Whilst the Chinese participants reported more of a negative or mixed emotion. In addition to saying yes, that's awe-inspiring, they also reported a little bit of fear. This paper as a positive step towards understanding how the experience of awe is different around the world, how different cultures have different lenses to understand these emotions. And it follows that if researchers who are looking to implement CSR initiatives, want to leverage the emotion of awe, it's important to be mindful of how cultures experience it differently. I think there's a lot of work to be done on helping people be aware of other people's conception of emotions like awe.

Craig L. Anderson presents the French premiere of "Operation Arctic Cure," screened at HEC Paris.

The study of awe is only a few decades old. Yet, it’s been recognized that awe can improve well-being, foster greater connection to others, encourage pro social behavior and reduce stress, at least in the United States context, as you said earlier. So, why does it remain relatively unknown still to this day?

Affective science, the study of emotions has been around for a long time and the earliest versions of that studied what's thought of is the basic emotions, right? The obvious ones being disgust, fear, anger, joy. And the reason that awe lagged behind is not because people weren't interested in awesome experiences. It was just approached in a different way. So, we've had the idea of the sublime in philosophical literature for centuries. Sociological studies of awe-inspiring leaders and social movements have also been present for decades. I think what changed and why the science of awe has made so much progress in the last 15 to 20 years is the decision to situate it in this emotion literature. Now you have this rich constellation of other emotional states that you can compare awe to in a very principled way; you have really focused findings. You can compare it to other positive emotions like joy and amusement or compassion. And if awe does promote pro sociability, then you have a really compelling story about what awe does differently from these other distinct emotional states. So situating awe in the emotion literature, I think, is the reason we’ve seen this big uptick in scientific empirical work on it.

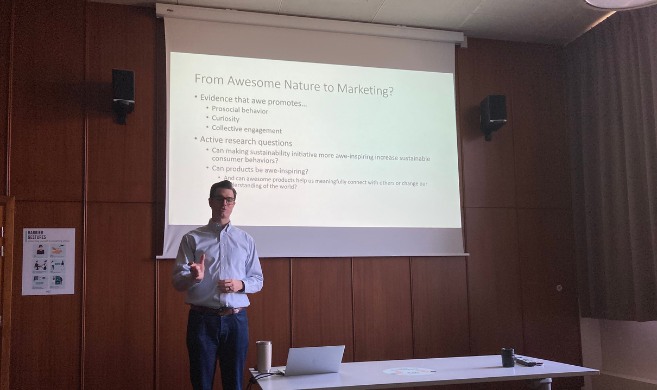

Craig L. Anderson presents his latest project on the use of awe in marketing in front of his HEC colleagues.

Let's turn to this more recent experience where you were looking at the healing effect awe on US veterans and their Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, PTSD. This resulted in your involvement in the 2024 National Geographic documentary “Operation Arctic Cure”. This had its French premiere here at HEC on November 4. This documentary covered a project by a journalist called Bob Woodruff, who accompanied a group of veterans on a voyage to the Arctic in extreme conditions to test if it could alleviate their symptoms of PTSD. Can you take some of this experience and integrate it into your own research, or is it just confirming things that your research suggests?

This whole experiment got me excited. Some of the measurement possibilities were unique because the technology of wearable devices has progressed so much since I did the white-water rafting work. Many of the veterans were wearing physiology monitors which allowed us to better understand the things we do in our daily lives, not just awe-inspiring things and the effects that it has on our bodies. I think this has given us a relatively untapped source of data. One thing that I always keep in mind is that awe is something that's not just for white-water rafting. It's not just for seeing the Northern Lights as they do in the documentary. My work now is looking to see how we can bring awe to the here-and-now, and how it impacts our day-to-day lives when we are given information about sustainability, for example.

My work now is looking to see how we can bring awe to the here-and-now, and how it impacts our day-to-day lives when we are given information about sustainability, for example.

That's when a lot of really important things happen. That's where most of our life happens. So that's what my research centers on now. I believe that awe and emotion that we associate with some of the most important and sacred things in our lives can also be an important agent for change as we strive against challenges like climate change and social inequality. I remain optimistic that, you know, work like this can help us move towards those goals.

Bob Woodruff speaks on ABC News about the National Geographic documentary "Operation Arctic Cure." The veteran reporter led a group of war veterans on a voyage to test a possible cure for their PTSD, inspired by the research of professors Craig L. Anderson, Maria Monroy, and Dacher Keltner. Read the article here.

References of the video extracts that you can hear in the podcast:

- National Geographic documentary “Operation Arctic Cure” (the French premiere at HEC)

- What Happens When We Experience ‘Awe’

- Jennifer Stellar: How Culture Shapes the Experience of Awe

Academic references:

- “Awe in nature heals: Evidence from military veterans, at-risk youth, and college students,” by Craig L. Anderson, Maria Monroy, and Dacher Keltner, published in the American Psychological Association, 2018.

- “Culture and Awe: Understanding Awe as a Mixed Emotion” by Craig L. Anderson, J. E. Stellar, Y. Bai, A. Gordon, G. D. McNeil, K. Peng, D. Keltner, published in Affective Science, 2024.

- "Awe, Daily Stress, and Elevated Life Satisfaction", by Bai, Y., Ocampo, J., Jin, G., Chen, S., Benet-Martinez, V., Monroy, M., Anderson, C., & Keltner, D., published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 120(4), 837–860, 2021.