The United Nations has recognized that global warming, essentially caused by human activities, has and continues to bring about numerous dramatic environmental, social and economic consequences. The adverse effects of greenhouse gas emissions (“GHG”), especially carbon dioxide, have only recently drawn significant attention despite the fact they had already been discovered by Joseph Fourier in the 19th century.

Listen to the podcast in French:

From 1979 to 1992: No clear obligations to limit carbon emissions

In 1979, the first World Climate Conference recognized that carbon dioxide produced by human activities was potentially dangerous, but it was not until the Earth Summit, held in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, that the international community became fully aware of the gravity of the situation and decided to take action. The Rio Declaration consisted of 27 principles intended to guide countries towards future sustainable development. In parallel, the Framework Convention1 laid the foundation for international cooperation in the face of climate change while developing the institutional framework for the Conferences of the Parties (commonly known as the “COP”). Unfortunately, the only coordination measure to be accepted was the setting of targets, which merely established a legal and institutional framework for the gradual development of a more operational international system, albeit one without any clear obligations weighing on industrialized countries.

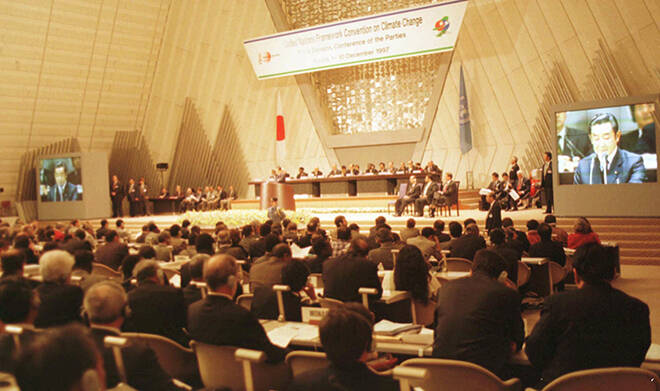

The Kyoto Protocol (1997): Birth of the cap-and-trade system but lacking of a long-term vision

The third COP held in Kyoto in 1997 put forward specific objectives to be attained. There, the industrialized countries committed themselves to reducing their GHG emissions by an average of 5.2% by 2012 compared with their 1990 levels as a reference. In order to ensure the effectiveness of these commitments, the Kyoto Protocol adopted a market-oriented approach via a cap-and-trade system. While it allocated a certain amount of international emission allowances per country, an emission allowance trading system was established so as to encourage States subject to the obligations of the Protocol to finance the reduction of GHG emission projects in other countries.

However, the Kyoto Protocol proved to be inadequate at reaching the expected goals due to the lack of incentives to encourage (non-Kyoto Protocol) countries to reduce their GHG emissions; as well as the lack of a long-term vision and its relative detachment from civil society.

When the EU took the lead in the carbon market

At the regional level, the European Union took the lead by establishing an emissions trading scheme through which European companies (rather than countries) can exchange emission allowances (the “EU Emission Trading Scheme,” or “EU ETS”), which now represents the world’s first major carbon market. Within the 2013-2020 period, the EU Member States pooled together their international obligations and set a common transnational objective for themselves (a reduction of 8% compared to 1990).

Auctioning is now the default method for allocating EU ETS allowances. Thanks to the Market Stability Reserve mechanism, the European Commission can freeze unallocated or surplus allowances in order to increase carbon prices. The recently adopted Directive 2018/410 revised the EU ETS for the 2021-2030 trading period. The new rules aim at accelerating emissions cuts, establishing better-targeted carbon leakage rules, and funding low-carbon innovation and energy sector modernization.

Local initiatives by governments and mayors: The largest global alliance for city climate leadership

At the local level, numerous initiatives put forward by sub-state entities (such as California or Quebec) have attempted to counterbalance the inaction of certain States and/or the weakness of the international system. The pioneering Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (“RGGI”) born in the 2000s between nine States in the Northeast of the United States eventually expanded to include New Jersey and Virginia.

The Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy is now the world's largest global alliance for city climate leadership.

Many cities have also committed themselves to developing and promoting renewable energy at their level of power. For example, more than 10,000 cities and local governments, together representing at least 800 million inhabitants, are now part of the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy, which is now the world’s largest global alliance for city climate leadership.

The Paris Agreement and latest COPs: Not ambitious enough?

As the Kyoto Protocol has only established targets for the initial period of 2008-2012, further COPs have attempted to renew and strengthen the commitments made therein (including its extension until 2020). These attempts ultimately paved the way for the Paris Agreement, which was adopted by 197 countries in 2015 during the COP21.

The Paris Agreement established an ambitious goal of limiting the increase in the global average temperature to “well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels.” The Agreement calls for national commitments to be reviewed every five years. Non-compliance is sanctioned, based primarily on a transparency and reputation mechanism with a committee of experts. The text focuses on developing methods and tools that are likely to yield results in the long term, although it does not establish a carbon market. Rather, it provides a broader, non-binding basis for international cooperation encompassing both market and policy approaches.

Finally, the Agreement was drafted and detailed using a bottom-up and decentralized approach. While only industrialized countries are required to pursue a quantified GHG emissions target, all of the contracting countries are required to determine, at their own national level, their contribution to the common goal of reducing GHG emissions.

The recurrent major international negotiations have made it possible to achieve a handful of limited agreements but have demonstrated the inability of States to commit to quantified objectives.

The recurrent major international negotiations have made it possible to achieve a handful of limited agreements but, above all, have demonstrated the inability of States to commit to quantified objectives, even though their violation of the agreement would be accompanied by actual, punitive measures.

During the last COP25 held in Madrid at the end of 2019, the lack of political consensus on rules for the establishment of an international carbon market led States to postpone (“table”) taking action on the issue until the next COP26.4 However, the encouraging news is that, in October 2020, China committed to achieving carbon neutrality by 2060 and is therefore relaunching the Paris agreement.

More globally, in its 2020 report, the World Bank listed 31 trading schemes that have been either implemented or are planned at the global level.3 Notably, South Africa became the first country in Africa to put a price on carbon and Latin America launched its first emissions trading scheme through Mexico’s three-year pilot.

So what would constitute an efficient solution?

The vast majority of carbon emissions at the global level is not tariffed or remains underpriced. Last year, the NGO Green Finance Observatory sent an open letter, signed by 88 academics around the world, to European leaders. Their conclusion is clear: “carbon markets will not make our planet great again.”5 So what would constitute an efficient solution?

We believe that the solution is not so about breaking with the market-oriented approach, but rather resting upon the improvement of the existing system.

We believe that the solution is not so much about breaking with the market-oriented approach, but rather improving the existing system. Given the urgency of the situation – and notably the irreversibility of climate-related changes – one cannot possibly entirely reconceive of the current system from scratch, so thus we believe it is more relevant to maintain it, while improving it through complementary measures.

(Photo Credits: ©Artram on Adobe Stock)

Any further delay in addressing the climate change problem could entail significant risks. The last report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (the "IPCC”) reveals that only half a degree of warming would be enough to have substantial negative impacts. For example, should there be an increase in temperature of 2°C, 37% of the world’s population could be exposed to severe heat waves within one to five years. If the temperature were to increase by 1.5°C, “only” 14%6 of the population would be affected.

In order to coordinate and connect the various existing initiatives, it is necessary to channel social actors (like government, civil society, and the business community) to act as a real force for change, and to improve the interlinkages between the various proliferative initiatives involving or surrounding carbon markets. Furthermore, this notion is based on the axiom of economic theory that the larger the market is, the more attractive it will be. Once linked, prices in these various systems will converge until they are ultimately identical.

In order to coordinate and connect the various existing initiatives, it is necessary to channel social actors to act as a real force for change.

This coordination could be facilitated through the use of new technologies such as distributed ledgers (“distributed registers”), of which the most well-known type is the blockchain. Since it operates without a central control body, the verification of the transferred content takes place via a peer-to-peer network. In fact, IBM and the Energy Blockchain Lab are already collaborating on the development of an emissions trading platform in China.

This coordination could be facilitated through the use of new technologies such as the blockchain.

In conclusion, the strengthening of existing carbon markets, the development of new allowance trading systems, and the combination of all these, aided by the use of new technologies and controlled and governed by a globalized civil society whose political power can no longer be overlooked, constitute, in our view, the way forward in the fight against global warming.

1For more details, see the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

2The United States, Canada, Japan, Member States of the European Union and countries of the former Eastern Bloc.

3World Bank Group, State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2020, Washington DC, May 2020.

4KPMG mentioned in its Key outcomes of COP25 - Briefing on the outcome of COP25, the 25th UN Climate Change Conference (December 2019) that the last COP was “widely seen as one of the most fractious and ultimately disappointing in terms of the progress it made”.

5Green Finance Observatory, Carbon markets will not make our planet great again – Addressing climate change requires sound environmental policies, not more failed carbon markets, 2019.

5IPCC, Global Warming of 1,5°C, 2018.