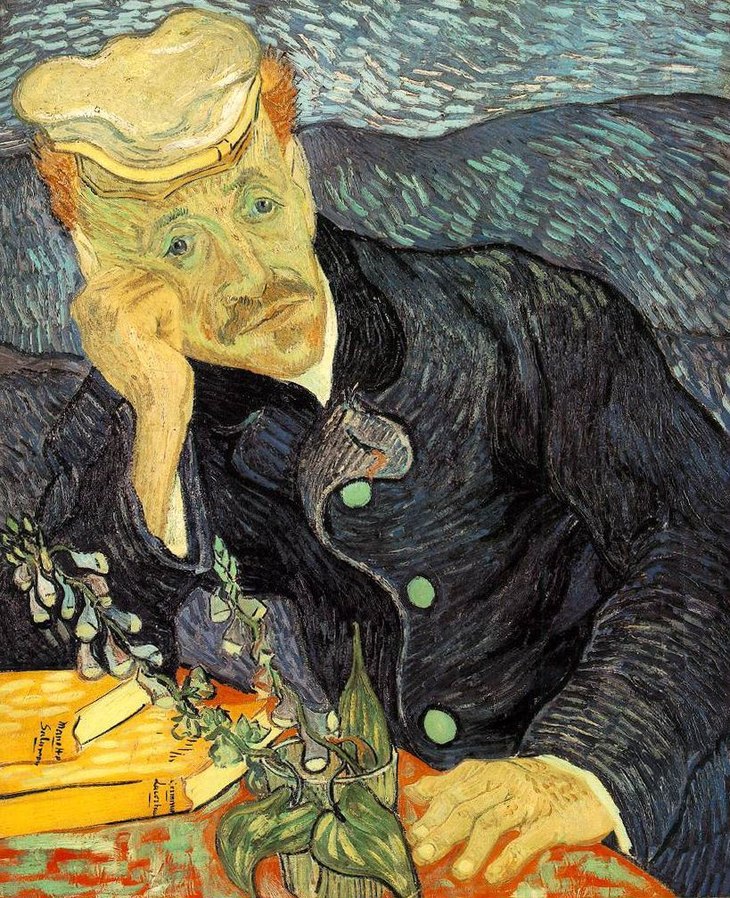

Wealthy individuals hold almost 10% of their wealth in “treasure assets” such as art, wine and jewellery collections, according to a 2012 study "Profit and Pleasure" by Barclays. The valuations of art are often shocking to the uninitiated and baffling to all but the most hardened art critic. A Jackson Pollock painting consisting of paint splattered on canvas sold for $200 million in 2015, placing it in the top five most valuable paintings of all time, according to Wikipedia. For comparison, in 1990, the Vincent van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr. Gachet was sold for a record $ 82.5 million.

If paint splattered on canvas can achieve such a high price, what are the characteristics of art as an investment? In order to establish whether art is a lucrative investment strategy, we created a model for predicting the behaviour of buyers and sellers at art auctions. We then tested our model using a dataset of 1.1 million auction sales at leading auction houses Christie’s and Sotheby’s in the United States and the United Kingdom between 1976 and 2015.

Art is not a normal financial asset

Our model had to take into account the two fundamental differences between a piece of art and a normal financial asset, the first difference being the type of payouts and the second the transaction cost.

Firstly, for a piece of art, the “dividend” that art pays is emotional rather than financial. Its value thus depends on the owner’s personal taste, unlike for example the cash dividends that you receive as a stock investor, or the income on a house that you rent out.

Secondly, trading art comes with high transaction costs. Auction houses will charge a fee on the hammer price as high as 25% for artworks costing under $200,000. This fee falls to around 12% for more expensive artworks.

If you like a painting, go for it, but be aware that if you like it a lot and pay accordingly, you are not very likely to sell it at a profit.

There are three types of art buyers: collectors, flippers, and investors

Another factor for our model was to consider that valuable art often lives longer than its owner and all owners, or their heirs, eventually sell.

We identify three types of behaviour in the art market. Collectors will typically spend vast amounts of money on the art that they want, they hold on to their piece of art for a long period, and sell only when they are forced to do so. As result, they typically sell at a loss.

Then there are the flippers who will buy art only when it is cheap and sell it quickly at a profit. Somewhere between these two extremes lie art investors, who will tend to buy at a medium price and sell only if the economic conditions are good enough.

If you don’t like a painting, don’t overbid, because you run the risk of being stuck with it.

Whether you behave as a collector, a flipper or an investor depends on how much you like the artwork compared to the average taste in the population. Collectors like their purchase the most, and flippers the least.

Differences in art investment returns

In line with our predictions, we found that the monetary profits from art sales were highest for those artworks resold—or “flipped”—within 1 to 2 years.

Such auctions are initiated by owners who had been able to buy at a very attractive price. Longer holding periods were associated with lower returns, caused by both higher purchase prices and lower resale prices. However, those who hold for long periods are precisely those who enjoy the highest emotional dividends.