Christine Lagarde: An unusually scrutinized nomination

Christine Lagarde became the fourth President of the European Central Bank on November 1, 2019, for an 8-year term. It is striking how many comments her nomination has drawn, on several different topics such as her unusual profile for the job, the politics of her nomination, or her first moves at the helm of the ECB.

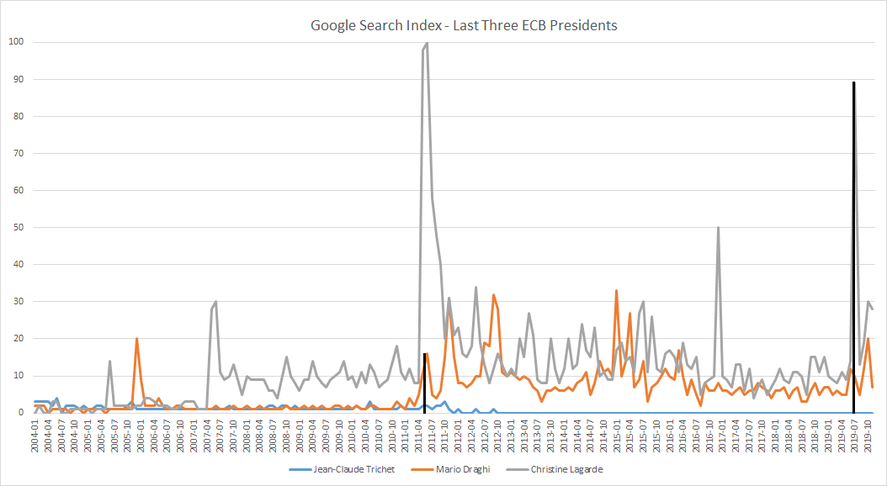

Such publicity is relatively unusual for a central banker. The “Google Trends” tool allows us to visualize this quantitatively by comparing the number of searches for Ms Lagarde and her predecessors, especially around the time of their nominations. There were six times more searches for “Christine Lagarde” around the time of her nomination this year than for “Mario Draghi” when he got the job in 2011. In contrast, Mr Trichet seems to have generated few searches during his tenure.

One should not of course draw too many conclusions from this crude analysis, but in my opinion it reflects an important trend: the position of President of the ECB is much more prominent and thus gets much more media attention today than was the case ten years ago. This is in large part due to Mario Draghi, whose media treatment during the euro area crisis created the perception that the President of the ECB was a sort of European superhero (“Super Mario”).

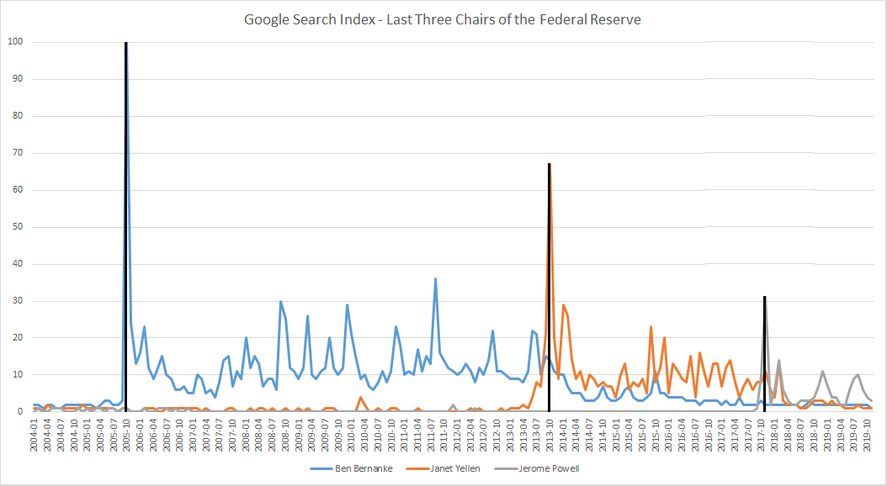

Interestingly, if one conducts the same exercise for the Federal Reserve, the opposite picture emerges: Ben Bernanke drew more attention in 2005 than Janet Yellen did in 2013, who in turn generated more searches than Jerome Powell in 2017.

The hypothesis I will develop here is that the trend observed for the ECB does not only reflect differences in personalities across ECB presidents, but rather may be due to a certain institutional fragility of the ECB. This problem has to do both with its young age for a central bank (after all, the ECB was still a teenager two years ago), and with the institutional difficulties of the euro area and the European Union.

What does a President of the ECB do?

When it comes to monetary policy decisions, in principle the President of the ECB is only the chair of a committee, the ECB Governing Council, which is made of the six members of the Executive Board of the ECB and the governors of the 19 national central banks of the euro area (only 15 of them have voting rights in a given month). Due to this structure, it is unlikely that the President of the ECB can act as a monarch, irrespective of his or her putative super-heroic abilities. Rather, the President has to be a dealmaker: the 19 national representatives are likely to be influenced by the situation of their own economy and to favor different policy decisions, especially when economic conditions diverge across the euro area. A consensus has to emerge from these different views, or at least a compromise, reflecting to the extent possible the “general interest” or the euro area. An interesting empirical study by Hayo and Méon (2013) confirms this view: they show that the interest rate decisions of the ECB over 1999-2006 are best explained by a model in which national governors follow their national objectives and bargain over the interest rate decision, the bargaining power of each country being proportional to its GDP. The situation of crisis countries then gained more weight during the sovereign debt crisis (Bouvet and King, 2013).

Ardent Europeans might lament this situation, as in principle all members of the ECB Governing Council are supposed to care about the interests of the euro area as a whole, not only of their home countries. While this situation may reflect the incompleteness of the political union of the euro area, it is worth noting that the same behavior is observed in the voting members of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), which plays a similar role as the ECB Governing Council and functions in much the same way: the presidents of at least some of the 12 Federal Reserve Banks display a systematic bias towards the macroeconomic conditions of their own district (Jung and Latsos, 2015).

The role of staff

Another reason to not overemphasize the importance of any individual central bank president is that central banks are organizations with a life of their own. There was much more continuity in policymaking between Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen and then between Janet Yellen and Jerome Powell than had been expected ex ante. The reason is that all three had to rely on the same staff and on the same well-established processes: the Federal Reserve System is a large organization with 19,500 employees in the 12 Federal Reserve Banks and another 2,900 at the Board of Governors in Washington. While the Fed has many different missions, a considerable part of the workforce is devoted to collecting information and statistics, analyzing, forecasting, and ultimately giving as much information as possible to the board and making policy recommendations. Romer and Romer (2008) show statistically that individual Federal Reserve Bank presidents do not seem to have any informational edge over these staff forecasts, and that when their monetary policy decisions differ from those implied by the forecasts they are in general misguided.

While such an empirical study does not exist for the euro area (due to lack of data), the European System of Central Banks relies similarly on the expertise of its staff, which is probably of similar quality and, if anything, more numerous (3,500 employees at the ECB, between 9,000 and 10,000 at both Bank of France and the Bundesbank, 6,700 at the Bank of Italy).1 As in the U.S., this staff produces an impressive quantity of data, reports, forecasts, and models to guide policy decisions, so that one would expect the results of Romer and Romer (2008) to hold in the euro area as well. While the role of the central bank’s president is certainly important, monetary policy decisions are the output of an entire institution.2