Eloïc Peyrache

Dean of HEC Paris

HEC scholars work with public and private regulators such as the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) and the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB), chaired by Emmanuel Faber, who recently told HEC students: “Don’t quit!”. They are joining forces with colleagues from leading European academic institutions in the Business School for Climate (BS4CL) collaboration to widely diffuse knowledge and increase awareness. They work with CEOs of the Business for Inclusive Growth coalition (B4IG) and members of the Institut Français des Administrateurs (the French Administrators Institute) to develop, test, and evaluate novel strategies, policies and practices designed to tackle inequalities in the field.

HEC scholars work with public and private regulators, peers from leading European academic institutions, CEOs and administrators to develop, test, and evaluate novel strategies, policies and practices designed to tackle inequalities in their field.

In this Knowledge@HEC issue, we share academic knowledge and highlight professional experiences through interviews. Strategy and Business Policy professors Marieke Huysentruyt and Bénédicte Faivre-Tavignot present their research and teaching; Finance researchers François Derrien and Maxime Bonelli reveal their key findings on the effect of ESG reports on employee’s investments. Camille Putois, Director of B4IG, and Gilles Vermot Desroches, Chief corporate of Citizenship and Institutional Relations at Schneider Electric, share their view and experiences of implementing ESG and measuring the impact of their initiatives.

Marieke Huysentruyt

Associate Professor of Strategy and Business Policy, and Academic Director of the Inclusive Economy Center at the S&O Institute

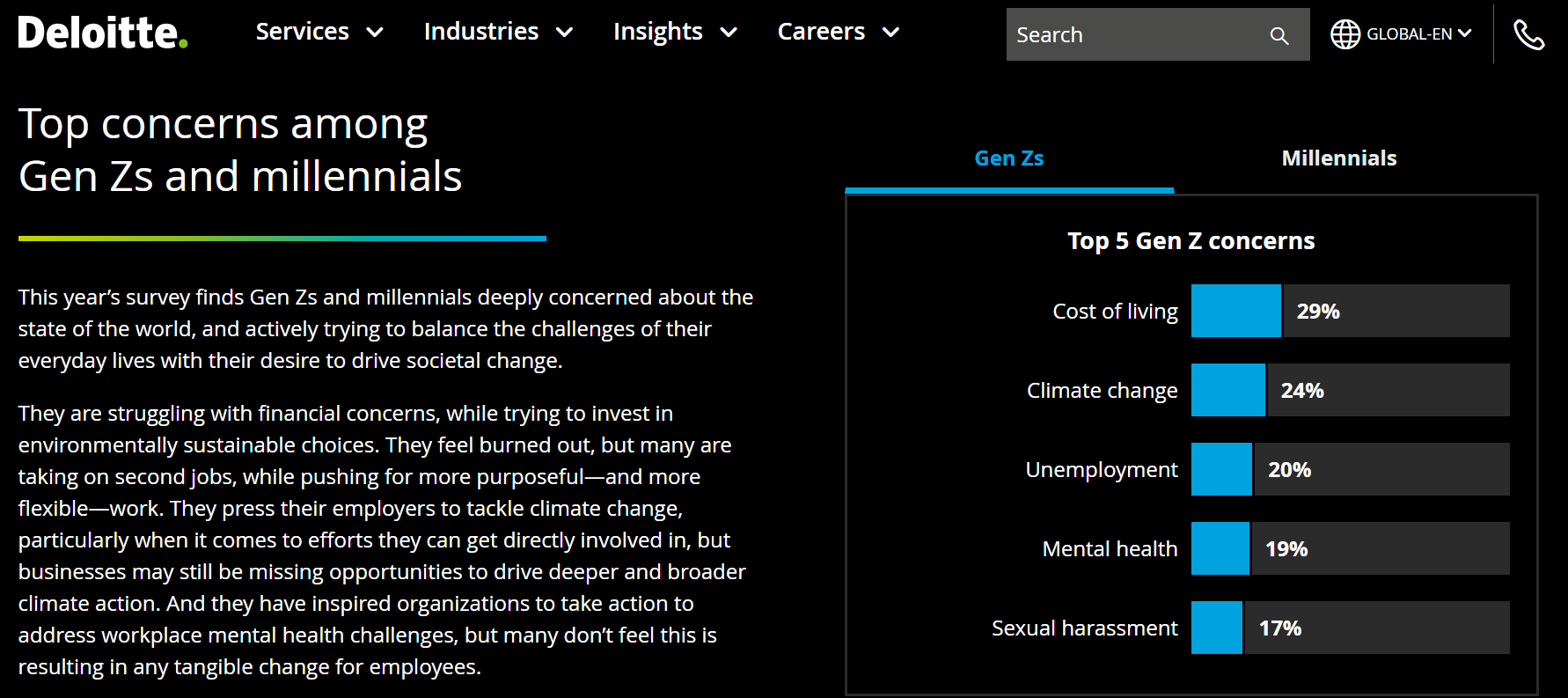

Companies’ sustainability or environmental, social and governance performance (ESG) has increasingly become a strategic consideration, a source of unique reputational, financial, and relational competitive advantage. The COVID-19 pandemic, the Yellow Vests protests and other social movements, the deepening and widening inequalities and economic crisis have put the ‘S’ side of business in stark relief. Today, companies are more than ever hard-pressed to be upfront and ambitious about their social impacts. ESG frameworks help companies take stock of their sustainability performance. And they are incredibly influential as they guide investment decisions.

Yet, we are just beginning to make sense of a complex set of ESG frameworks. Working with Standard & Poor’s Global Ratings’ researcher Bruce Thomson, we find that when it comes to the coverage of the ‘S’ factor in ESG, the major ESG frameworks don’t all agree or align. For example, while companies are always asked to consider their employment conditions, not all ESG frameworks require companies to consider their social impact along the entire value chain. Yet, companies are part of an ecosystem, and thus need to address human rights of supply chain workers and their impacts in the communities where they operate.

Companies are part of an ecosystem, and thus need to address human rights of supply chain workers and their impacts in the communities where they operate.

In that system, the ecological transition needs to be socially fair to be efficient. As Gilles Vermot Desroches of Schneider Electric notes: “We won’t make progress on climate matters if we do not harmonize our value chain and, therefore, human rights issues. There must be respect to all our staffs, as well as those who work for our suppliers, and for our suppliers’ suppliers, etc.”

Furthermore, some social challenges, such as the forced migration and refugee crisis, are not covered at all by ESG frameworks. Being aware of these differences and limitations, knowing which combination of ESG frameworks yields a more holistic view of a company’s social performance is a foundational step, a basis for improving our understanding.

Europe is busy preparing a new set of sustainability standards that will become law, in all likelihood around January 2024. These standards will be a game changer as they oblige companies of a certain size to publicly report on a whole host of ESG criteria in a systematic and comparable way. The transparency and broad coverage of all ESG factors (double materiality) surely will help improve the accountability and credibility of business, and push companies to walk the talk.

"The performance of companies in relation to ESG standards helps socially conscious investors screen their investments. Such considerations are becoming increasingly important to investors," note Finance researchers François Derrien and Maxime Bonelli.